In the previous part of this series on Testing Effect and teaching strategies, we talked about Finland's strategies to get to the top tier of educationally elite countries. We talked about the country's history and how the Finnish government ensured things moved fast and in the right direction. In this final installment of the series, we shall talk about Nepal and where we stand in terms of educational strategies locally and at the governmental levels.

Furthermore, we shall also talk about our findings regarding the prevalence of the Testing Effect and teaching strategies. With a lot of attention now focused on education because of the realities of a pandemic stricken world, this conversation suddenly becomes important. We must ask ourselves if we are doing enough. Or do we need a lot more than what we already have?

Introduction to the Nepali Education World

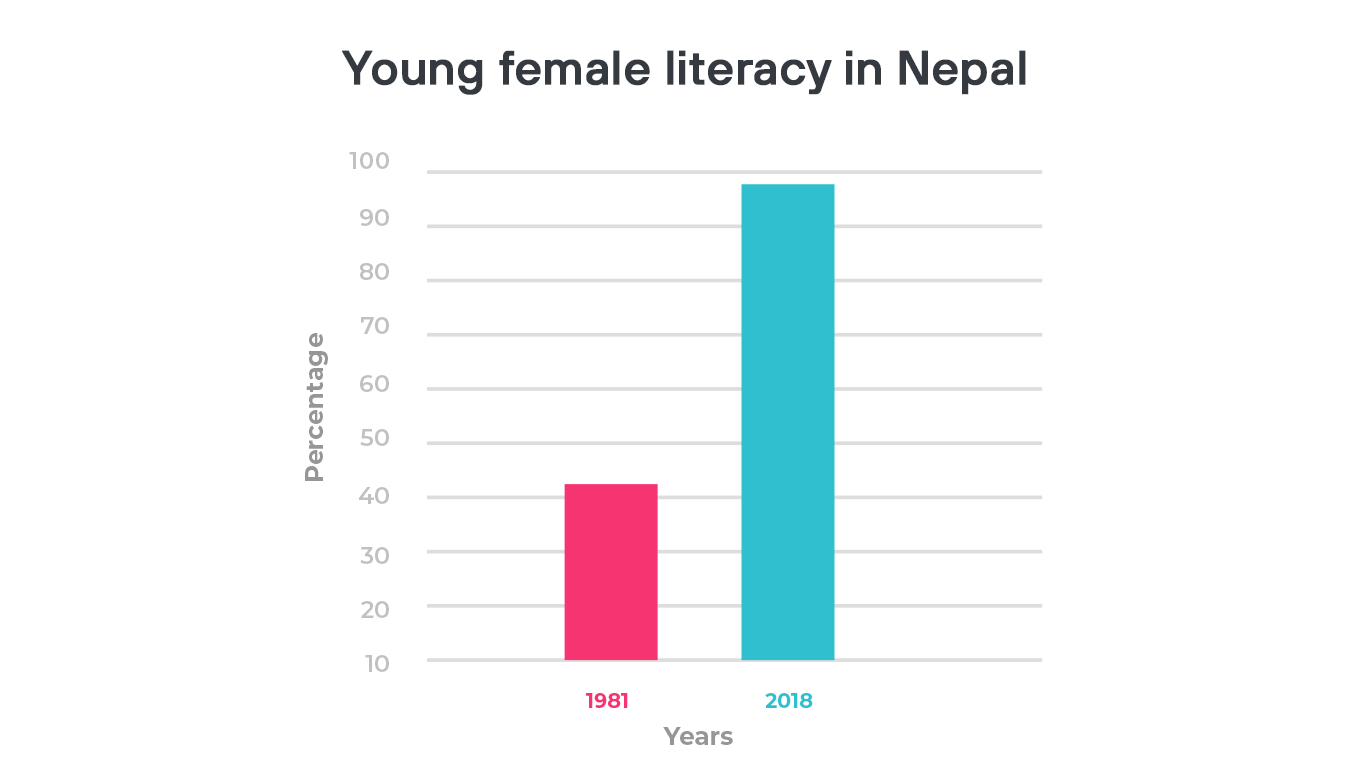

Nepal has made good progress in terms of education and literacy in the last decade itself. The adult literacy rate of Nepal grows at an average of 30.06 percent yearly (World bank, September 2018). Additionally, gender disparity in education has been swiftly decreasing, especially in the urban areas, with the percentage of literate women (15-24) years sitting at 90.88 percent. [Source]

Despite encouraging numbers, it has been argued that the quality of education hasn't been up to the mark. A World Bank study in 2017 noted that education in Nepal is too focused on memorization and text regurgitation [Source]. Critical thinking is given less importance, and analysis and creativity are often neglected in the process.

The SSDP 2016-2023

To address the concerns surrounding rote learning, among many others, the Nepali government came up with the School Sector Development Program 2016-2023 to improve the quality of education. The plan categorizes skills into three subcategories: soft skills, life skills, and core skills. Despite the effort, Staufenberg and Tweedale, in their research, noted that skill appeared to have a much 'lower priority than knowledge' [Source].

Skinner, Blum, and Bourn, in their 2013 research, noted that this knowledge over skill seems to be a common thought pattern in developing countries. Since these countries seem to be more focused on getting more and more people into schools, the actual activity of learning is often compromised. This phenomenon seems understandable and unacceptable at the same time.

On top of all this, the SSDP includes a section for Examinations and Assessments, which is sort of the core for our blog series here. However, the government's interpretation of examinations seems to be limited to end-term assessments that aim to label an individual 'qualified' rather than assessments that aid learning. The idea of testing as an 'enabler', as opposed to a 'determiner', seems to be missing altogether. Because of that, ultimately, even teachers would miss out on essential training, and we would yet be unaware of just what else testing can help achieve.

The Picture of Testing In Nepal

Section 3.2 of the SSDP notes the introduction of CAS (continuous assessment of students). However, the document also notes that CAS is yet to be ‘fully comprehended by parents and teachers to be implemented over summative exams [source].

Our survey found out that about 20 percent of teachers were unaware of the term 'Testing Effect'. Of the teachers who were aware, only 42.3 percent thought that testing students before a class/topic was more, or equally effective to testing students at the end. In Part 2 of this Testing Effect series, we noted that 'Feedback' was a necessary intervention in terms of determining the success of the testing strategy. In Veda's survey, however, only 46.3 percent of teachers picked feedback over examinations. 32.9 percent thought exams were the best way to move forward, while the remaining 20.8 percent were unsure.

Despite that, one positive we found was that 85.7 percent of teachers still like to test their students before starting a topic. Regardless of their understanding of the Testing Effect, many teachers believe that testing students before class enable students to better understand the topic being covered. In addition to that, teachers also believe that by testing students before class, teachers could develop strategies as to how a topic should be approached. This strategy would be based on how students did in the pre-topic test.

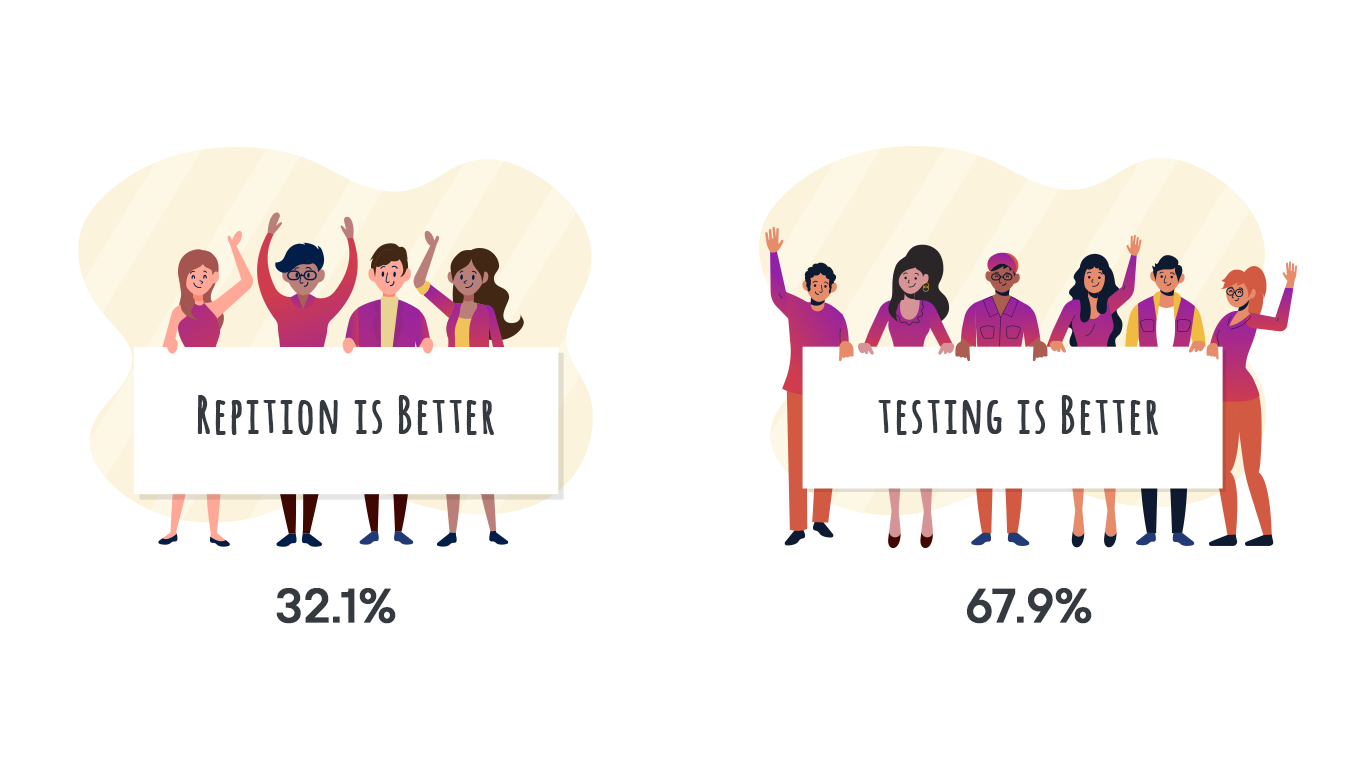

Finally, when asked to evaluate repetition and testing, 32.1 percent of teachers thought repetition was better, despite 96.4 percent believing that testing improved retention in the earlier section. This irregularity could suggest that teachers aren't a hundred percent confident about what methods to follow in class. More parameters need to be considered to cement such an observation. However, the lack of clarity suggests improper training, guidelines, and support from the government.

Teaching and Learning Strategies in Nepal

Although the government recognizes the problems, the solutions offered in the SSDP are vague at best. For instance, under Strategic Intervention for Examinations and Assessment, the most significant solution proposed is 'standardized testing'. If you have followed this series, in Part 3, we talked extensively about Finland's strategies and how they made progress by getting rid of standardized testing. A counterargument to this, however, is the state of public schools in Nepal. If not for standardized testing, the disparity between private and public schools would be too intense to disappear. For context, the passing rate for public schools is just over 30 percent, while that for private schools is 50 percent.

The SSDP also recognizes that quality and effective pedagogy leads to better learning outcomes. The results have been disappointing, however. Despite teachers receiving the necessary training, the pedagogy remains historic for the most part. The British model of education as a means to preserve colonial influence has dominated education at large. As a result, we're producing a workforce who can understand and obey instead of those who can understand and evaluate.

Under Strategic Intervention, the SSDP notes that the evolution of pedagogy shouldn't be looked at as an external intervention but as an integral part of the system itself.

Although having recognized 'testing' as a necessary teaching strategy, our survey revealed that teachers still think STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) students benefit more from testing than arts and humanities students. Furthermore, almost 90 percent of teachers believe that they should be strict with students in addition to being compassionate and supportive. These observations are sort of reinforcing an outdated conscience still plagued by the rigid times from whence it came into being.

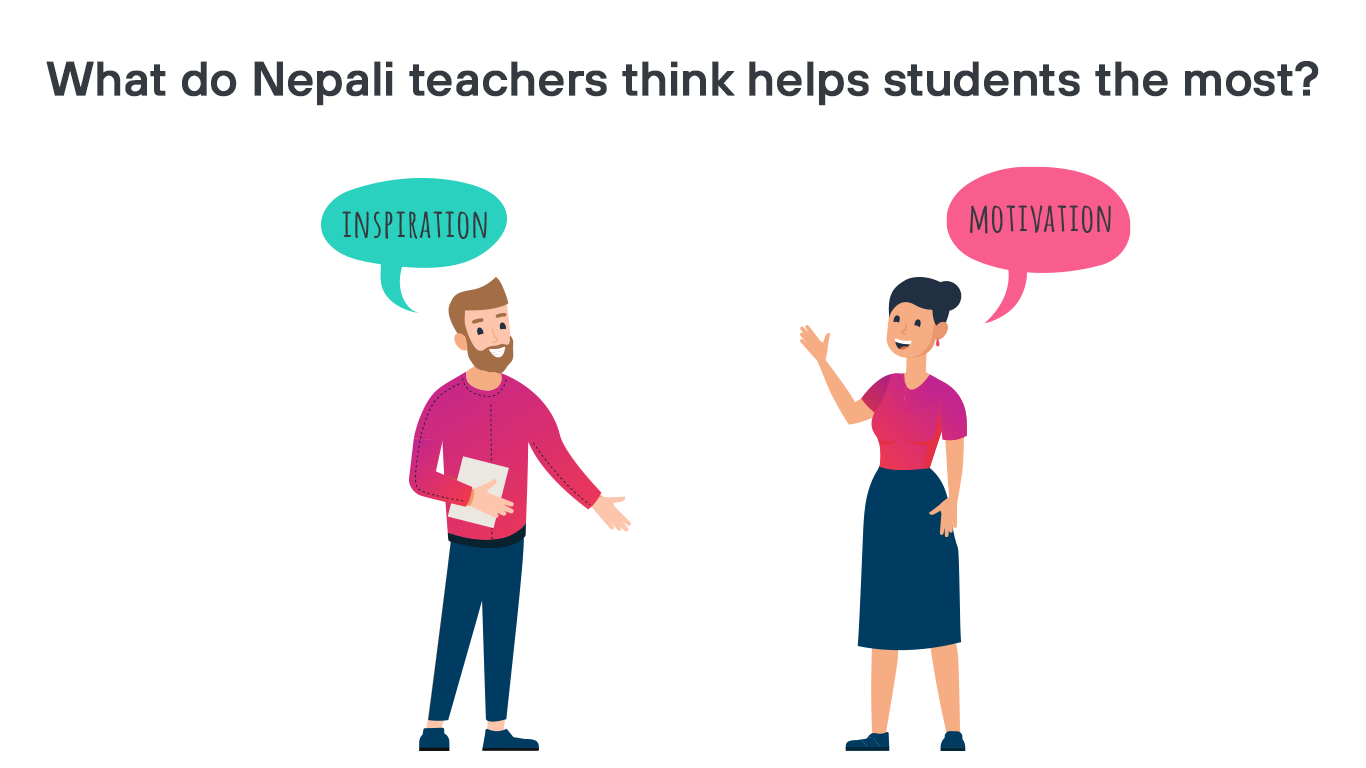

Finally, a comprehensive word-based evaluation of teachers' response to the question "What do you think can be done to improve Student's retention? Please share with us briefly" revealed that most teachers value 'inspiration' and 'motivation' over anything else. That alone was enough for the team at Veda to see the light into the future. As the software did its thing, we patiently waited through our biases of expecting 'test', 'learn', 'exam' or 'result'. However, we were proven wrong. Still, despite the optimism around motivation and inspiration, why do we still find ourselves struggling with the quality of education?

We are here to help

Since 2015, Veda has been actively working to ensure that education evolves to new highs. We share a vision of accessible, just, and sustainable education for everyone. We are consistently conducting necessary experiments and innovating to ensure that education is better than it was yesterday. Veda organizes events, provides training to teachers and parents and ensures there is no disruption when it comes to education.

Veda hopes to bridge the gap between private and public schools through the integration of technology.Currently as of writing with 650+ schools in Nepal using our School management software. This gap is one of the most prominent factors stopping a seamless transition into a system backed by quality over quantity. Veda hopes to contribute its best in helping Nepal reach complete literacy, so we can then focus more on strategies and curriculum.

As a first step, Veda organized Haat, Haat ma Shikshya event powered by Khalti Digital Wallet to reduce the gap between students and teachers of a different class, caste, race, gender, and creed. Veda trained more than 20,000 teachers under its Digital Literacy drive. Additionally, more than 200,000 parents have been trained so far as well. This ensures that parents and teachers are able to navigate their way around technology and find ways to help children achieve the best!

Do let us know your thoughts about this series on Testing Effect through comments. You can also support us by sharing this with your friends, hopefully opening up conversations, if nothing else. Thank you for making it to the end. We will keep bringing you content like this in the future, so make sure to stay tuned. Happy learning!